June Mushroom of the Month: Ganoderma sessile

The June mushroom of the month is Ganoderma sessile or Reishi!

What is It?

Ganoderma sessile is a recently re-named species of Reishi found in north America. Previously it was known as Ganoderma lucidum, the species commonly referred to as Reishi found in Asia and Europe. However, recent genealogical evidence has indicated that the north American variety is a unique species.

WHAT CHANGED?

For many years, Ganoderma sessile was considered to be Ganoderma lucidum. Research published in 2018 by Loyd et al found that Ganoderma lucidum was in fact only native to two places in North America, Utah and northern Califorina, and is likely a non-native species introducted accidently by cultivators. Ganoderma sessile is a related species native to North America.

IS ALL REISHI THE SAME?

Species of Ganoderma, commonly called reishi (in Japan) or lingzhi (in China), have been used in traditional medicine for thousands of years. Research by Loyd et al has shown that products labeled as ‘reishi’ often contain a mix of species from this genus, including G. applanatum, G. australe, G. gibbosum, G. sessile, and G. sinense. There is likely differences between the species in terms of potency but more research is needed.

BECOME A SUPPORTING MEMBER & stay Dialed in with events & discover next month’s mystery mushroom

8 Ways to Learn to Identify & Forage Wild Mushrooms

We are in peak foraging season with the recent rain. We have several resources we recommend you check out.

We are in peak foraging season with the RECENT rain. We have several resources we recommend you check out.

🌐 Visit our website and take the online foraging mushrooms class. It comes with a foraging calendar download.

📝 Visit our blog for the latest foraging forecasts and tips on how to take photos of mushrooms for positive identification.

🥾 Check our calendar for upcoming mushroom walks we have a 🔦UV night walk coming up soon.

🔪 Check out the latest issue of Texas Monthly to learn about foraging wood blewits

🧺 The Texas Parks & Wildlife Magazine also has lots of great article in their March issue on foraging mushrooms.

♉ Join us at Texas Mushroom Conference late this month, forage.atx will be keynoting on Foraging Mushrooms in Texas.

🏷️ Tag us to get help with ID and add your observations to iNaturalist.org. If you are trying a new mushroom, confirm the ID with a human expert. Always cook, then try a small amount to make sure you don't have a reaction.

📋 Become a member and learn more about wild mushroom foraging in Texas! Membership benefits include early access and discounts to walks, workshops, and more. Your membership helps support the larger community!

May Mushroom of the Month: Favolus or Honeycomb Fungus

The May mushroom of the month is the tropical and edible Favolus species

What is It?

This genus of white rot fungus is saphrophytic with head hardwoods in Eurasia, Japan, Africa, Central and South America and the southern areas of North America. There are currently 25 distinct species within this genus, all sharing a distinct honeycomb shaped gill structure from which it derives its common name, honeycomb fungus.

Is it edible?

Honeycomb fungus is not considered a choice edible mostly because of the texture. However, in 2020 a paper was published on the commercial cultivation, nutrition and food potential of this tropical mushroom in the Amazon where it is native and collected by the Yanomami people, who already sell more than 10 Amazon mushroom species. You can learn more about their mushroom culture in this film by @beatrizmaues.

Foraging Tips

Look for honeycomb fungus on the trunks and base of dead and rotting hardwoods, such as oak and pecan in central and east Texas.The best time to harvest is when the fungus is soft and fresh, before they have begun to harden and turn yellow. Check this months foraging forecast on our blog for more tips on cooking with this shroom from @forage.atx!

BECOME A SUPPORTING MEMBER & stay Dialed in with events & discover next month’s mystery mushroom

A History of Circular Innovation: Repurposing Spent Spawn Blocks from Mushroom Farms in Austin, Texas

Daniel Reyes reflects on the 2013 origins of our block waste diversion program, it's a testament to the power of perseverance and community working to change the value of what is considered waste.

By: Daniel Reyes, co-founder of CTMS and founder of Myco Alliance

Join us online for a class with Daniel about Applied Mycology.

Back in 2013, while working as a hydrogeologist in the oil and gas industry, I reached out to my friend Mike Wolfert for advice on mushroom cultivation. Little did I know, this simple conversation would spark a massive change in the course of my career. Mike Wolfert, known for his work in regenerative agriculture and permaculture through organizations like Symbiosis TX (formerly One World Permaculture), became a key figure in my journey. Over the course of several months, I kept looking for opportunities to learn all I could about mycology while I kept my career job.

I did a lot of self learning until I heard about these guys out by Dripping Springs who were growing edible mushrooms. I started volunteering on the weekends at LoGro Farms, where I marveled at their innovative approach to sustainability. There, the circular economy was alive and thriving: Jester King Brewery sent their spent beer rains to LoGro, where they were repurposed as substrate for mushroom cultivation. LoGro then produced mushrooms from this waste, which became a key ingredient in tanley's pizza and a staple in Jester King's famous Snorkel mushroom beer. This closed-loop system not only minimized waste but also maximized resource efficiency, inspiring me to rethink waste management in the mushroom farming industry.

While volunteering at LoGro Farms, where sustainability thrived as a core principle, I stumbled upon a notable hurdle: spent mycelium blocks, cast aside after only a handful of harvests. As I observed the stacks of discarded mycelium blocks from the production of their mushroom kits, it became clear that there was more to their story than mere waste. These blocks, once bursting with life as a vital component of mushroom cultivation, now languished in neglect, awaiting their fate in the discard pile. Yet, amidst their apparent insignificance, I saw a hidden opportunity—an opportunity to breathe new life into these discarded remnants.

I went back to Mike and suggested we could put these discarded blocks to good use in a project. I explained how these blocks, instead of being thrown away, could be used to strengthen swales and berms. Mike was intrigued. We brainstormed ways to make it happen, considering how these blocks could improve soil health and help plants grow. By incorporating spent mycelium blocks into swales and berms, we aimed to enhance their functionality and ecological benefits. The mycelium, with its intricate network of hyphae, acts as a natural binder, strengthening soil structure and promoting water etention. As these blocks break down over time, they contribute organic matter and nutrients to the surrounding soil, enriching its fertility and supporting plant growth.

In pursuit of expanding my knowledge and impact in the realm of applied mycology and environmental remediation, I journeyed to the Ecuadorian Amazon basin later that year into the Sucumbios region. Drawing from my background in hydrogeology and having been recently inoculated with the ethos of circularity nurtured at LoGro Farms and guided by Mike's wisdom in permaculture practices, I endeavored to seamlessly intertwine these ideologies in the Ecuadorian context.

Navigating the complexities of Amazonian ecosystems and addressing environmental challenges. We initiated projects to strengthen resilience and promote sustainable living practices. One of the key challenges we faced was sourcing suitable spawn for our projects. While commercial strains were readily available in the capital city of Quito, they were ill-suited for the unique conditions of the Amazon. We recognized the importance of using native strains, tolerant to the region's environment, to ensure the success of our initiatives and for that reason began to work only with producers of native, resilient strains.

Against the backdrop of environmental degradation and industrial impact, we were acutely aware of the region's history, including the devastating legacy of Texaco's oil drilling operations in the Lago Agrio oil field. Texaco's irresponsible waste disposal practices in the 1960’s, amounting to billions of gallons of oil dumped into unlined pits, had left a lasting scar on the ecosystem, poisoning water supplies and threatening indigenous livelihoods.

In 2015, following my return from Ecuador, I initiated pioneering research through Myco Alliance LLC on the use of mycelium for bioremediation. It wasn’t until 2016, however, that a significant breakthrough occurred. Together with Ecology Action of Texas, we secured a $50k grant from the National Fish and Wildlife Foundation for the Montopolis Wetland and Creek Rehab Project. This project was centered at the Circle Acres Nature Preserve, once a capped landfill and now a 10-acre expanse of restored wetlands,forest, and grassland nestled within the southeast Austin neighborhood of Montopolis.

The acquisition of this grant and the subsequent construction of The Research Stationmarked a pivotal moment in our journey. It provided the impetus for the development of educational programming focused on waste diversion. What better place to lead such efforts than at an old landfill site?

Between 2016 and 2019, our educational initiatives at Myco Alliance flourished, particularly with the invaluable addition of Hi-Fi Mycology to the burgeoning Austin mycology scene in February of 2017. The collaboration with Cory and Sean was instrumental during those years, which would end up leading to the formation of the Central Texas Mycological Society in 2019. Those days though, on average, I along with volunteers, would pick up anywhere between 300-700 blocks per week from their farm near 183 and Burnett. Each block averages about 5 lbs so we were essentially diverging close to 1 ton of spent spawn per week and close to 50 tons of annual waste diverted from landfills. These blocks would instead end up at Circle Acres, at the mycological research station, and get used multiple times.

At our mycological research station at Circle Acres, the journey of these blocks took on various stages. Upon arrival, they rested in our greenhouse, allowing the mycelium to rejuvenate for subsequent mushroom flushes. This process yielded approximately 40 lbs of mushrooms per week, which I distributed to volunteers and local food spots like Curcuma and Bento Picnic on E. Chavez in Austin. This distribution not only provided sustenance but also served as an educational opportunity for volunteers and students attending our classes.

Once the mushrooms were harvested, the blocks were stripped of their plastic bags. Some blocks were broken up for workshops, while others were placed directly into the ground at the demonstration gardens of the research station. These intact blocks retained their structural integrity, maintaining the fungal lamination crucial for fruitbody development. Consequently, patches of mushrooms consistently dotted our grounds. After approximately two flushes in the ground, these blocks were unearthed and repurposed in restoration projects around the site, particularly in areas prone to erosion due to increased urbanization.

During this time, Austin was experiencing rapid urbanization, leading to a surge in impervious cover and exacerbating issues with stormwater runoff and erosion. This not only affected the stability of the landfill cap but also impacted riparian zones adjacent to the site. The influx of impervious surfaces amplified the volume and velocity of stormwater runoff, resulting in erosion along waterways and compromising the integrity of surrounding ecosystems.

Amidst these challenges, our restoration projects, fueled by the repurposed mycelium blocks, played a crucial role in mitigating erosion and fostering ecological resilience. By strategically placing these blocks in erosion-prone areas and riparian zones, we were able to enhance soil stability, reduce sedimentation in water bodies, and promote the regeneration of native vegetation. This holistic approach to restoration, coupled with community engagement and education initiatives, contributed to the sustainable stewardship of our natural landscapes in the face of urban development pressures.

In the summer of 2019, the Central Texas Mycological Society (CTMS) emerged from he foundation laid by Myco Alliance, marking a significant transition in our journey. Building upon this milestone, we launched the Mushroom Block Giveaway program, which continues to thrive to this day.

Through this program, we collaborate with local mushroom farms to repurpose "spent" mushroom blocks, diverting them from waste streams. These blocks, once destined for disposal, are now valuable resources for cultivating mushrooms and nurturing healthy, fungal-rich soil. The initiative not only addresses waste reduction but also promotes education and community engagement.

In conclusion, the evolution of the block waste diversion program underscores the transformative potential of grassroots initiatives and community-driven solutions. From its inception at Myco Alliance to its integration into the fabric of the Central Texas Mycological Society, this journey highlights the importance of persistence, collaboration, and innovation in creating positive environmental impact. As we reflect on the history of this program, we are reminded of the profound lessons learned and the enduring legacy of our collective efforts towards a more sustainable future.

As stewards of environmental sustainability, we invite you to support our mission by donating, becoming a member, or volunteering your time. Together, we can continue to make a positive impact on our ecosystem and inspire others to embrace sustainable practices.

April Mushroom of the Month: Trametes sanguineas, Cinnabar Bracket

The April mushroom of the month is 𝘛𝘳𝘢𝘮𝘦𝘵𝘦𝘴 𝘴𝘢𝘯𝘨𝘶𝘪𝘯𝘦𝘢, the The blood red bracket!

The April mushroom of the month is 𝘛𝘳𝘢𝘮𝘦𝘵𝘦𝘴 𝘴𝘢𝘯𝘨𝘶𝘪𝘯𝘦𝘢, the The blood red bracket! Scroll to learn about this fascinating mushroom!

Congrats to Dr. Carole for naming that mushroom correctly and becoming the 1,319th member of Central Texas Mycology!

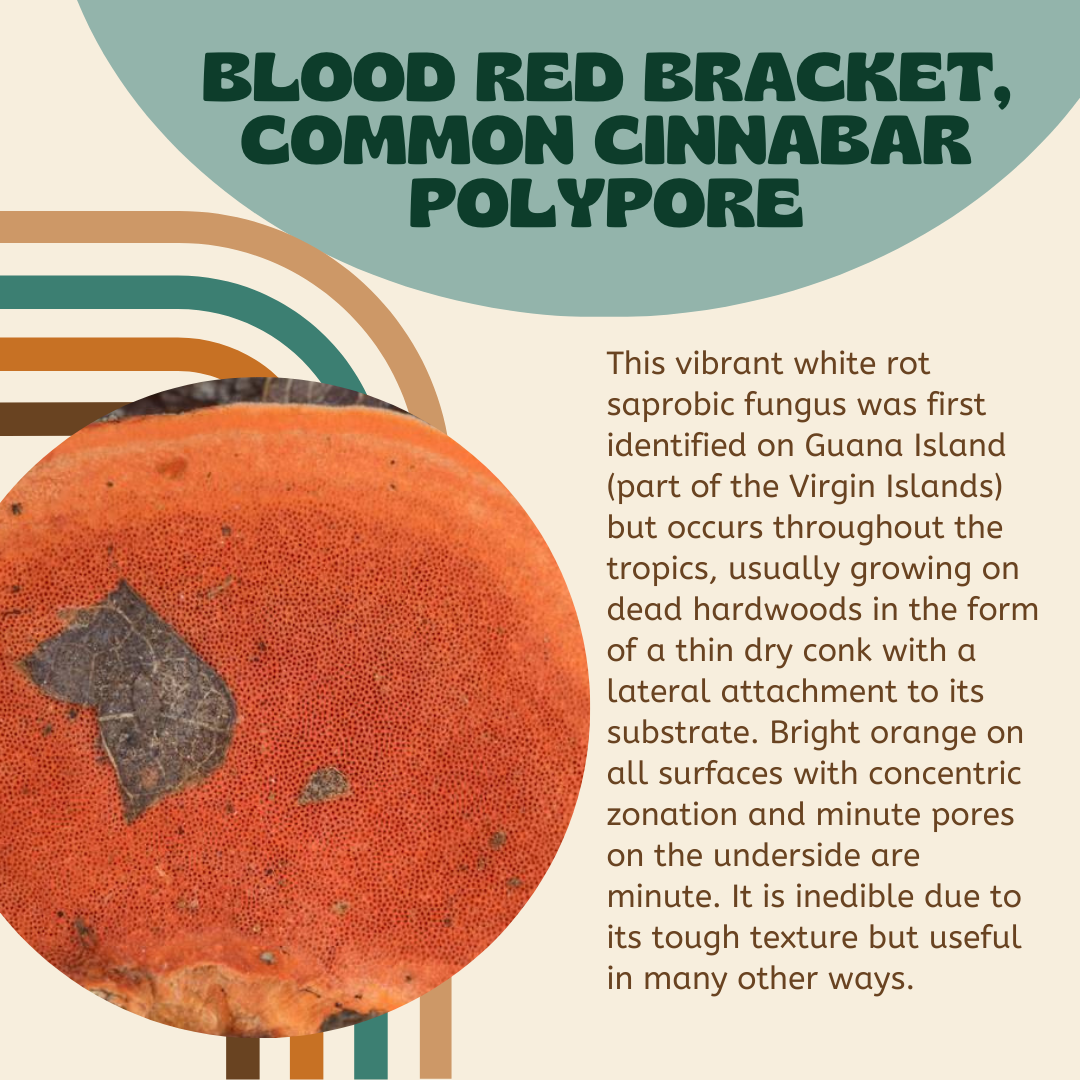

blood red bracket, Common Cinnabar Polypore

This vibrant white rot saprobic fungus was first identified on Guana Island (part of the Virgin Islands) but occurs throughout the tropics, usually growing on dead hardwoods in the form of a thin dry conk with a lateral attachment to its substrate. Bright orange on all surfaces with concentric zonation and minute pores on the underside are minute. It is inedible due to its tough texture but useful in many other ways.

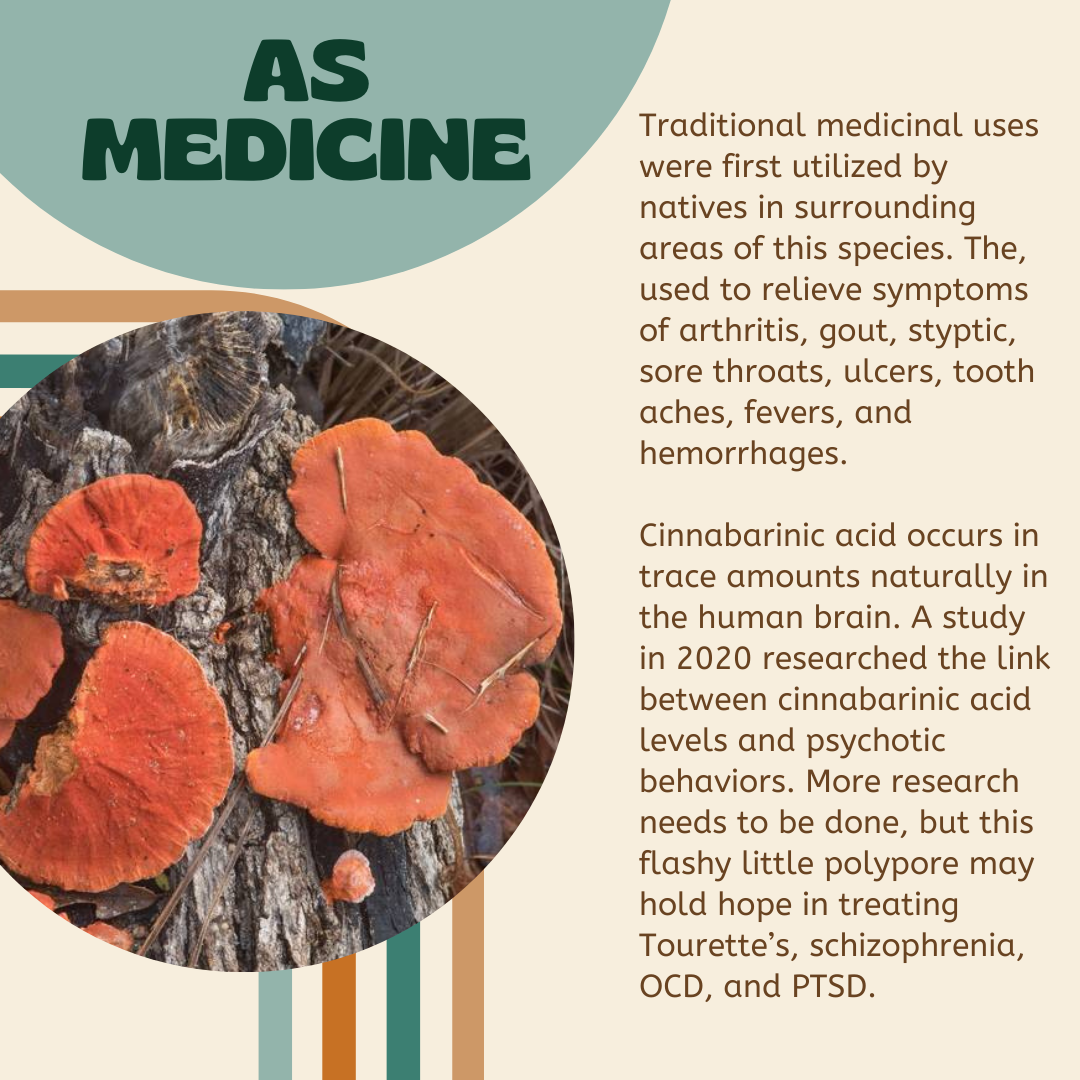

as medicine

Traditional medicinal uses were first utilized by natives in surrounding areas of this species. The, used to relieve symptoms of arthritis, gout, styptic, sore throats, ulcers, tooth aches, fevers, and hemorrhages.

Cinnabarinic acid occurs in trace amounts naturally in the human brain. A study in 2020 researched the link between cinnabarinic acid levels and psychotic behaviors. More research needs to be done, but this flashy little polypore may hold hope in treating Tourette’s, schizophrenia, OCD, and PTSD.

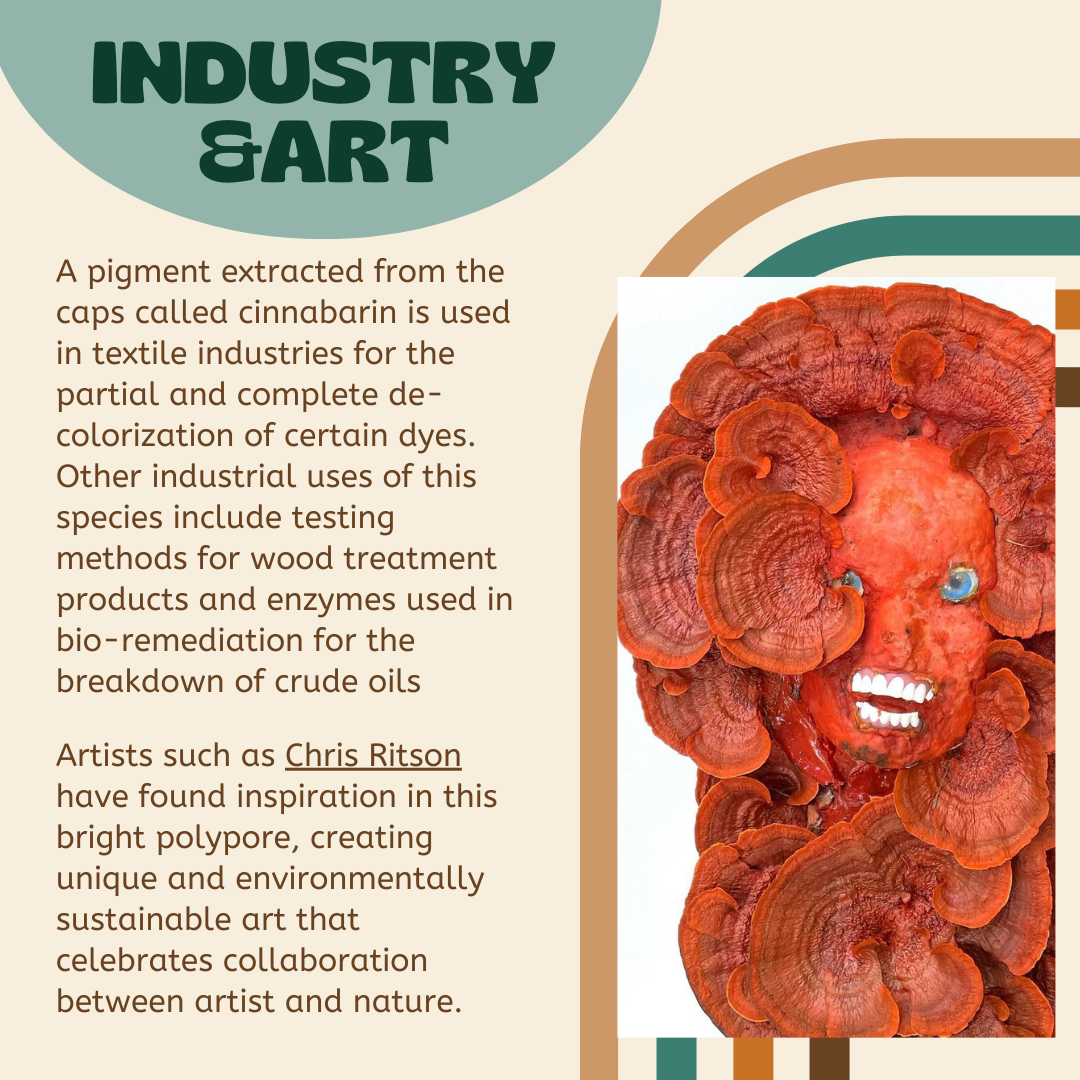

industry & art

A pigment extracted from the caps called cinnabarin is used in textile industries for the partial and complete de-colorization of certain dyes. Other industrial uses of this species include testing methods for wood treatment products and enzymes used in bio-remediation for the breakdown of crude oils

Artists such as Chris Ritson have found inspiration in this bright polypore, creating unique and environmentally sustainable art that celebrates collaboration between artist and nature.

Become a supporting member to stay dialed-in with events & discover next month’s mystery mushroom.

April Foraging Forecast

Learn wild, edible mushrooms fruiting in Central Texas after rain.

Learn wild, edible mushrooms fruiting in Central Texas after rain.

Shoehorn Oyster Mushrooms

Hohenbuehelia petaloides

Fruits after rain in mulch or woody debris

Considered carnivorous because it traps nematodes with “sticky knobs” in the mycelium to obtain nitrogen and grow.

Edible when cooked but can be tough and mealy

Shoehorn Oyster Mushrooms, Hohenbuehelia petaloides is distinctively shaped; its "petaloid" habit often makes it look like a shoehorn with gills, or a rolled-up funnel. Other identifying features include its fairly crowded whitish gills, a white spore print, mealy odor and taste—and, under the microscope, gorgeous "metuloids" (thick-walled pleurocystidia). It often appears in clusters in urban, semi-urban, or even household settings, and is frequently associated with woody debris (though it does not usually grow directly from dead wood) or cultivated soil. However, it can be found in woodland settings, too, where it tends to grow alone or in small groups.

Because this mushroom grows in wood chips which are a good source of carbon but a terrible source of nitrogen, the fungi needs to make proteins. Both Hohenbuehelia and Pleurotus can supplement their protein needs by trapping and consuming nematodes, which are small flat worms that are very abundant in wood and soil. The fungi have "sticky knobs" on the hyphae that grow through the wood. These sticky knobs attach to curious nematodes as the nematodes attempt to eat the mycelium. The nematode thrashes around and additional parts of its body become stuck. The hyphae then grow into the body of the nematode and digest it, providing the fungus with the nitrogen it needs. That makes these fungi carnivorous!

Look-alikes: Oyster mushrooms, Pluerotus speciestions?place_id=18&subview=map&taxon_id=48496 or Lentinellus cochleatus (none observed in Texas) but grow on decomposing wood.

WOOD BLEWIT Collybia species, formerly Lepista, Clitocybe

Distinct lilac to purple-pink color

Grows in and decomposes leaf duff

Light pink to white spores

Great in breakfast tacos

As the weather stays cool, look out for the edible Wood Blewit, Collybia nuda or tarda species (formerly Lepista and Clitocybe.) This distinct lavender-colored mushroom is found from fall through spring and fruiting in hardwood leaf duff which is decomposes. Fresh wood blewits are great with eggs in breakfast tacos. As they get older they become more tan and iridescent colored on the cap and taste bitter. I throw the older wood blewits my compost leaf pile because they are such great decomposers and will colonize and grow in hardwood leaf litter.

Look-alikes: Be warned because there are deadly, poisonous look-alikes in the Cortinarius or webcap family that grow in similar conditions. It's important to do a spore print AND also confirm the ID with an expert. The spores of the wood blewit are light pink to white and the spores of Cortinarius mushrooms are rust colored. See our blog post with lots of photos and details to help you identify this mushroom.

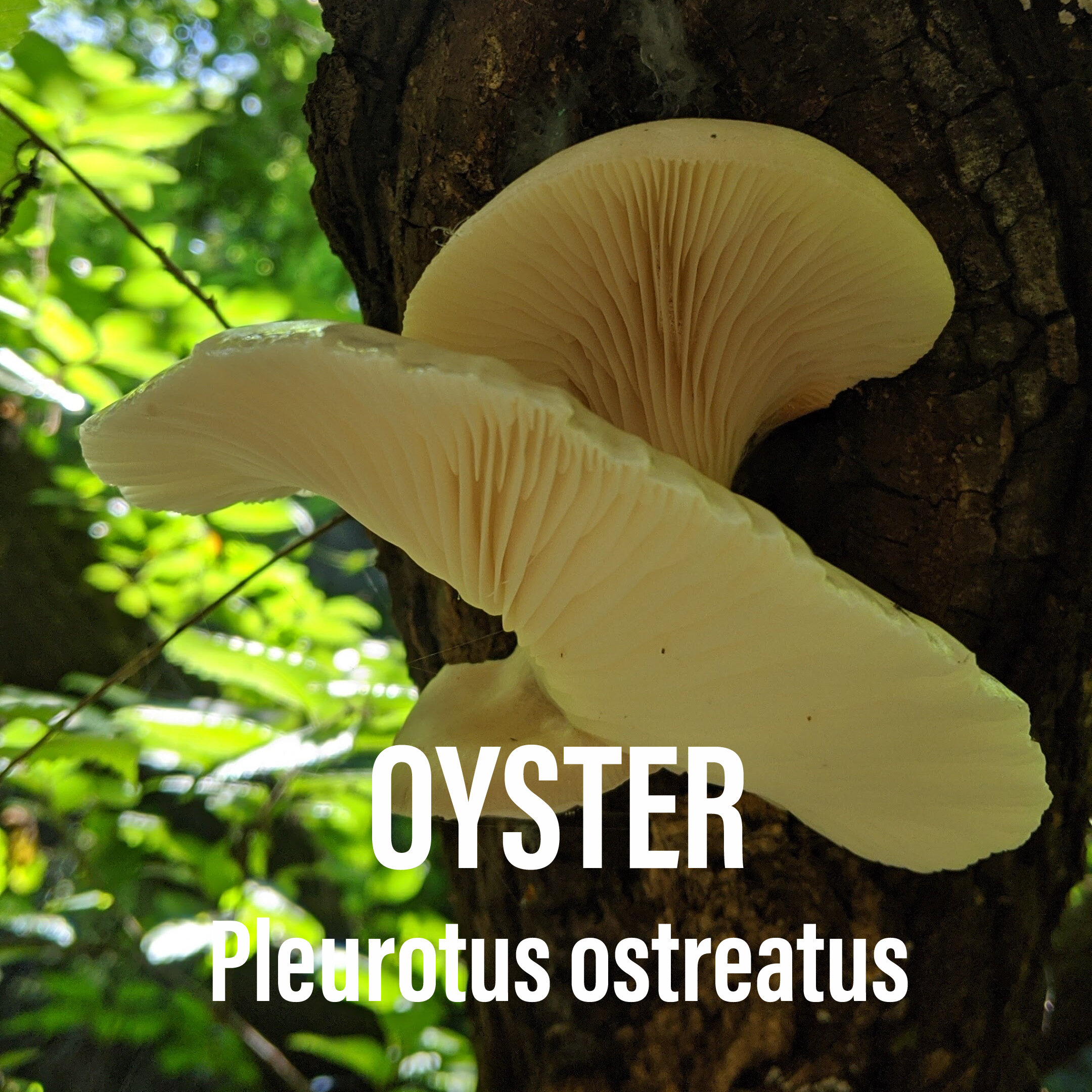

OYSTER Pleurotus ostreatus

Color can vary white, tan and gray

White to cream gills, run down stem

Cap fan shaped, 2"-8" across, white spores

Grows in clusters and decomposes hardwood

Delicious meat replacement in all types of cuisines

Look-alikes: Southern Jack-o-lantern, Omphalotus subilludens which is toxic and orange to brown in color.

WOOD EAR: Auricularia species

Grows in clusters on decaying hardwood after rain

Cap is wavy, ear-shaped to irregular, 1-4" and > 1/4" thick

Jelly texture and lacks gills or pores

Produces white spores

Absorbs flavors, great in soups, contains protein, iron, calcium and phosphorus

Edibility: Wood ear mushrooms are a popular ingredient in many Chinese dishes, such as hot and sour soup, and also used in Chinese medicine. It is also used in Ghana, as a blood tonic. Modern research into possible medical applications has variously concluded that wood ear has anti-tumor, hypoglycemic, anticoagulant and cholesterol-lowering properties.

Look-alikes: Amber Jelly, Exidia recisa which is also edible.

TURKEY TAIL Trametes versicolor

Variable coloration, distinct striping pattern

Grows in overlapping clusters on logs and stumps

No gills, pores are small and round, white to light brown

Tough, leathery flesh

Medicinal and can be brewed into a tea, broth, or extracted into a tincture.

Look-alikes: False turkey tail. or Stereum ostrea and is non-toxic. Mushroom Expert has a useful check list to determine if it is true medicinal turkey tail.

Become a member and learn more about wild mushroom foraging in Texas!

Membership benefits include early access and discounts to walks, workshops, and more. Your membership helps support the larger community! Tag us to get help with ID and add your observations to iNaturalist.org. If you are trying a new mushroom, confirm the ID with an expert, then try a small amount to make sure you don't have an allergic reaction. Texas Mushroom Identification Facebook group is great for quick responses and ID help. Also, don't forget to add your finds on the Mushrooms of Texas project on iNaturalist.

Follow my adventures @forage.atx.

March Mushroom of the Month: Shaggy Ink Cap

The March mushroom of the month is 𝘊𝘰𝘱𝘳𝘪𝘯𝘶𝘴 𝘤𝘰𝘮𝘢𝘵𝘶𝘴, the Shaggy Ink Cap!.

The March mushroom of the month is 𝘊𝘰𝘱𝘳𝘪𝘯𝘶𝘴 𝘤𝘰𝘮𝘢𝘵𝘶𝘴, the Shaggy Ink Cap!.

🙌 to Jeff for naming that mushroom correctly and becoming the 1,293th member of Central Texas Mycology! Become a supporting member to stay dialed-in with events & discover next month’s mystery mushroom.

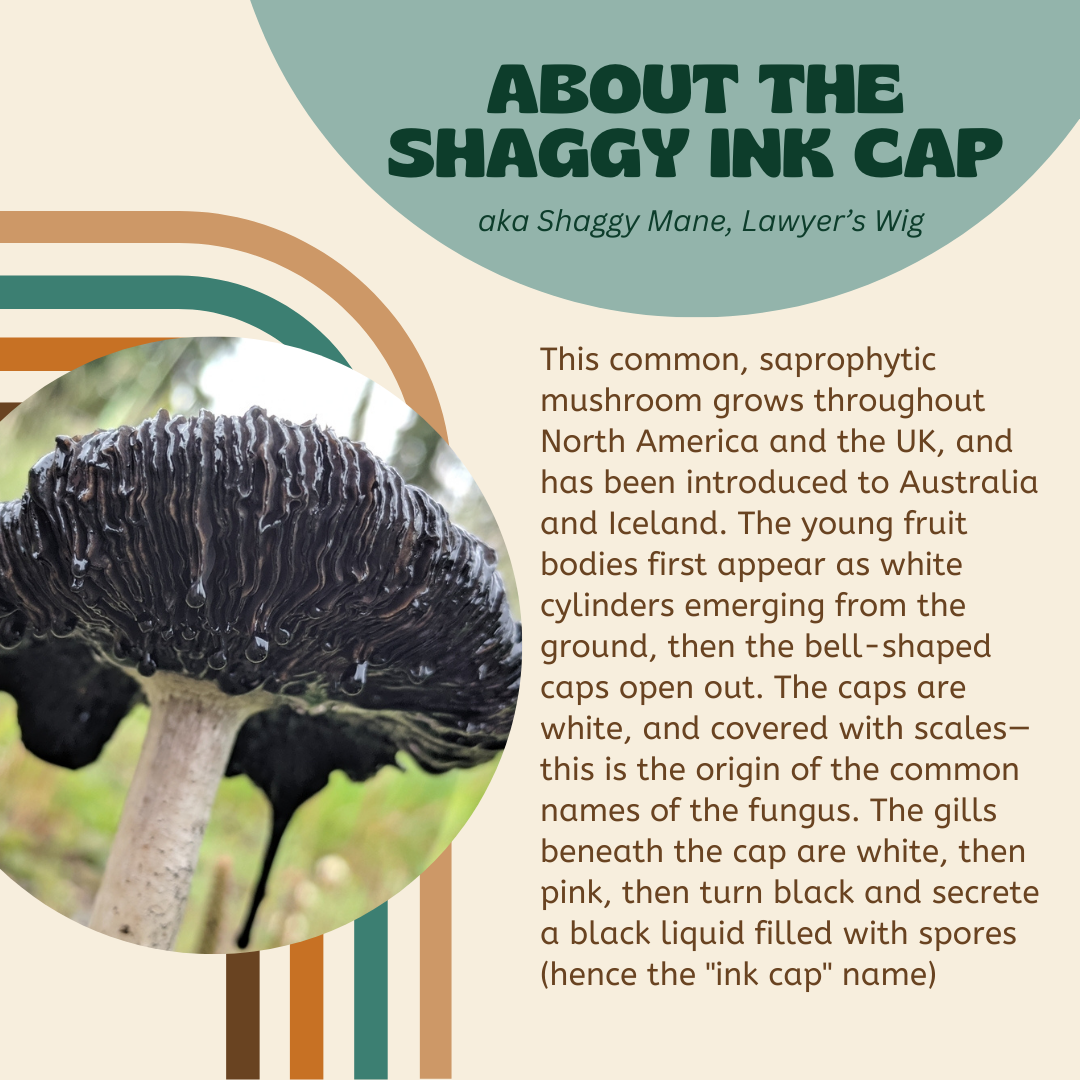

About the Shaggy INK CAP

aka Shaggy Mane, Lawyer’s Wig

This common, saprophytic mushroom grows throughout North America and the UK, and has been introduced to Australia and Iceland. The young fruit bodies first appear as white cylinders emerging from the ground, then the bell-shaped caps open out. The caps are white, and covered with scales—this is the origin of the common names of the fungus. The gills beneath the cap are white, then pink, then turn black and secrete a black liquid filled with spores (hence the "ink cap" name)

CAN I EAT IT?

Absolutely

The shaggy ink cap is an edible mushroom that was a part of the culinary experience in generations past. It must be harvested when young because it dissolves itself in a matter of hours after being picked in order to spread its spores. A recipe featuring it appears in the 1899 cookbook “One Hundred Mushroom Receipts.” The flavor is mild and cooking produces a great deal of liquid. Large quantities of microwaved-then-frozen shaggy manes can be used as the liquid component of risotto, replacing the usual chicken stock

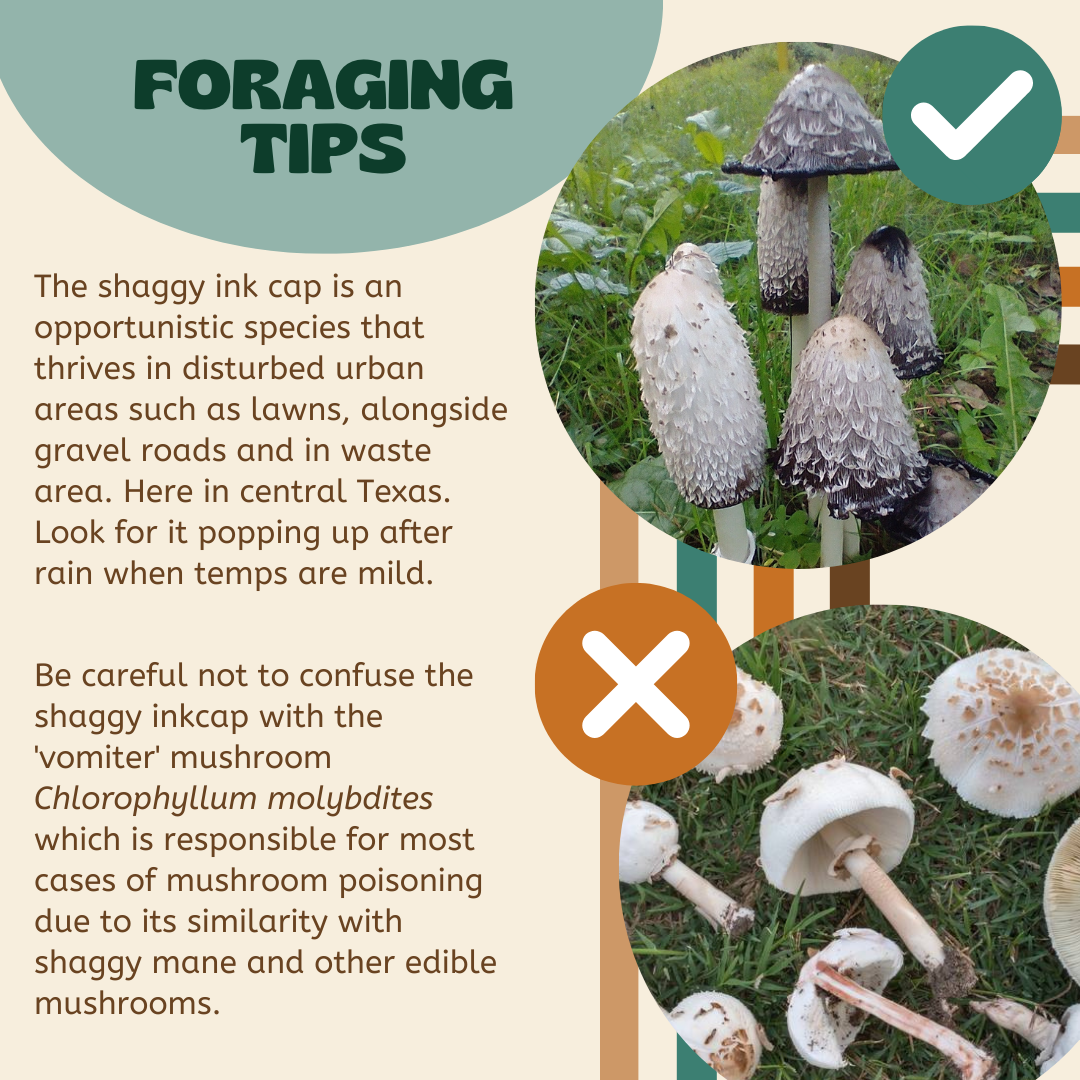

Foraging tips

The shaggy ink cap is an opportunistic species that thrives in disturbed urban areas such as lawns, alongside gravel roads and in waste area. Here in central Texas. Look for it popping up after rain when temps are mild.

Be careful not to confuse the shaggy inkcap with the 'vomiter' mushroom Chlorophyllum molybdites which is responsible for most cases of mushroom poisoning due to its similarity with shaggy mane and other edible mushrooms.

BECOME A SUPPORTING MEMBER & stay Dialed in with events & discover next month’s mystery mushroom

📸 @inaturalistorg

RECIPE: Chocolate Dipped Candied Wood Ear Mushroom

One of my favorite recipes to bring to Central Texas Mycology events are chocolate-dipped candied wood ears. Aricularia is one of the mushrooms that we have been seeing out on our walks and is in our forage forecast and you can learn more about how and when to find them and correctly identify them. Wood ear mushrooms have a lot of amazing benefits medicinally like thinning the blood and providing UV protection. It looks like they my have aphrodisiac effects as well. Wood ears also soak up a lot of flavor and you can use many types of juices and teas and for this recipe I used Mush Love: Reishi, Hibiscus and Ginger tea which are all aphrodisiacs.

Ingredients

6 oz. of fresh wood ear mushrooms (around 1-3 oz. dried) You can also buy wood ears Asian grocery stores or online. Sometimes they are labeled “black fungus.”

2-3 cups of juice or tea. See Mush Love Tea recipe for a double dose of mushrooms

1 12 oz. bag of vegan chocolate chips

Instructions

If you are using dried mushrooms (skip to step 2 using fresh mushrooms) soak the mushrooms in warm water until they are dark, shiny, jelly-like and have increased in size.

Bring a pot of water to boil. Add boiling water to a bowl of the wood ear mushrooms and soak for 3 minutes. Once they’re done, drain and briefly shock under cool water.

Place the mushrooms in a large bowl, and cover with a juice or tea like cranberry, pomegranate, or blue berry and place in the fridge for at least four hours (overnight is better). I soaked them in mush love tea, of hibiscus, ginger and reishi all aphrodisiacs. Recipe 😘

Remove the mushrooms from the fridge and strain out the liquid, shaking well. Line a baking sheet with wax paper and put in freezer to harden up.

In a microwave-safe bowl or using a double boiler, heat the chocolate chips for 30 seconds in the microwave or a few minutes over the stove. Take out and stir. Continue heating for 30 seconds at a time and stirring until the chocolate is smooth and fluid. Take one mushroom at a time and use a cloth or paper towel to pat the mushroom completely dry. Then dip one side into the melted chocolate.

Place the dipped chocolates directly onto the lined baking tray, and place the filled trays in the refrigerator for at least 15 minutes. Store any mushrooms you wish to save in air-tight containers in the refrigerator.

Follow my adventures @forage.atx.

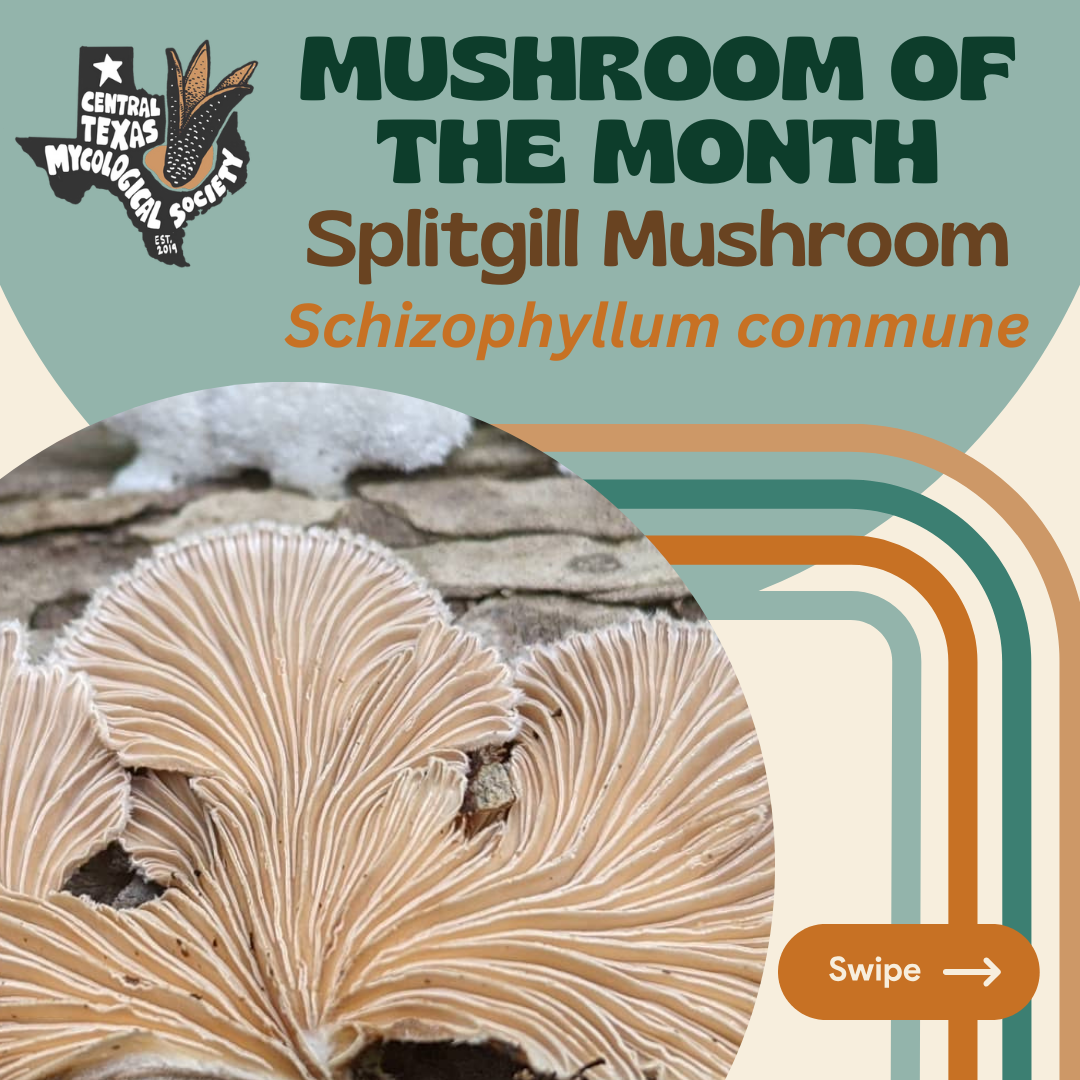

February Mushroom of the Month: Schizophyllum commune

The February mushroom of the month is Schizophyllum commune, the splitgill mushroom.

The February mushroom of the month is Schizophyllum commune, the splitgill mushroom.

🙌 to @elizabethoh for naming that mushroom correctly and becoming the 1,274th member of Central Texas Mycology! Become a supporting member to stay dialed-in with events & discover next month’s mystery mushroom.

What IS it?

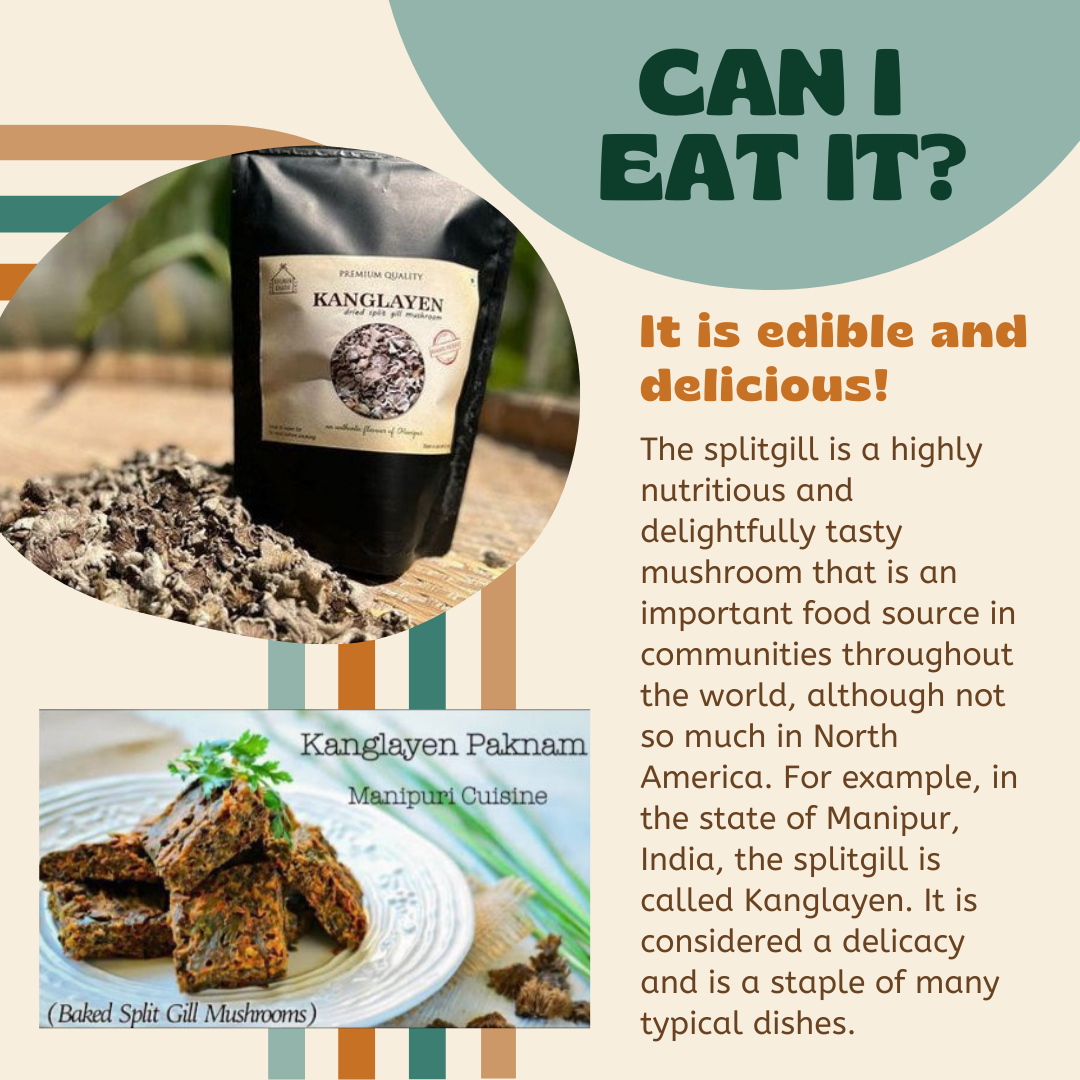

It is edible and delicious!

The splitgill is a highly nutritious and delightfully tasty mushroom that is an important food source in communities throughout the world, although not so much in North America. For example, in the state of Manipur, India, the splitgill is called Kanglayen. It is considered a delicacy and is a staple of many typical dishes.

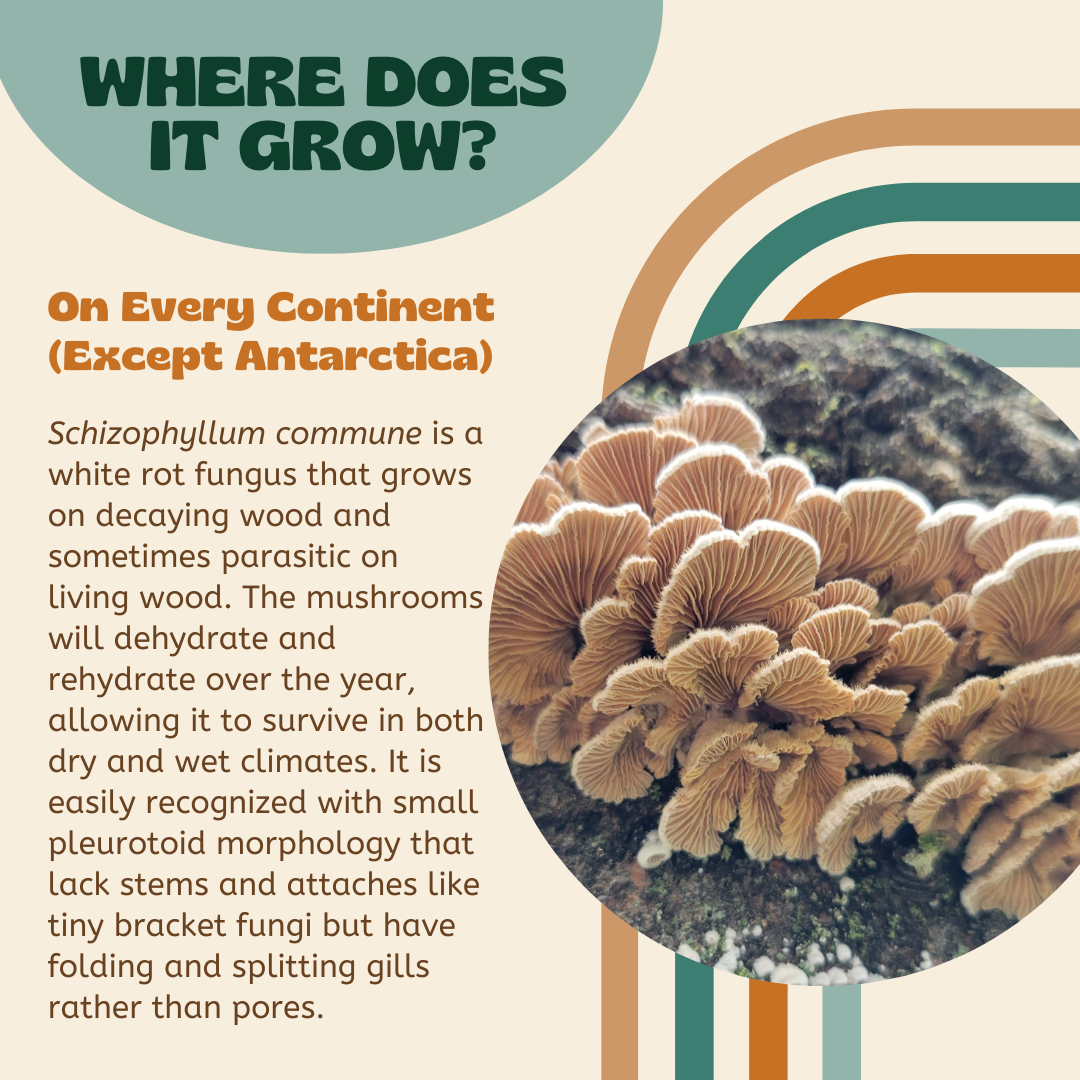

WHERE DOES IT GROW?

On Every Continent (Except Antarctica)

Schizophyllum commune is a white rot fungus that grows on decaying wood and sometimes parasitic on living wood. The mushrooms will dehydrate and rehydrate over the year, allowing it to survive in both dry and wet climates. It is easily recognized with small pleurotoid morphology that lack stems and attaches like tiny bracket fungi but have folding and splitting gills rather than pores.

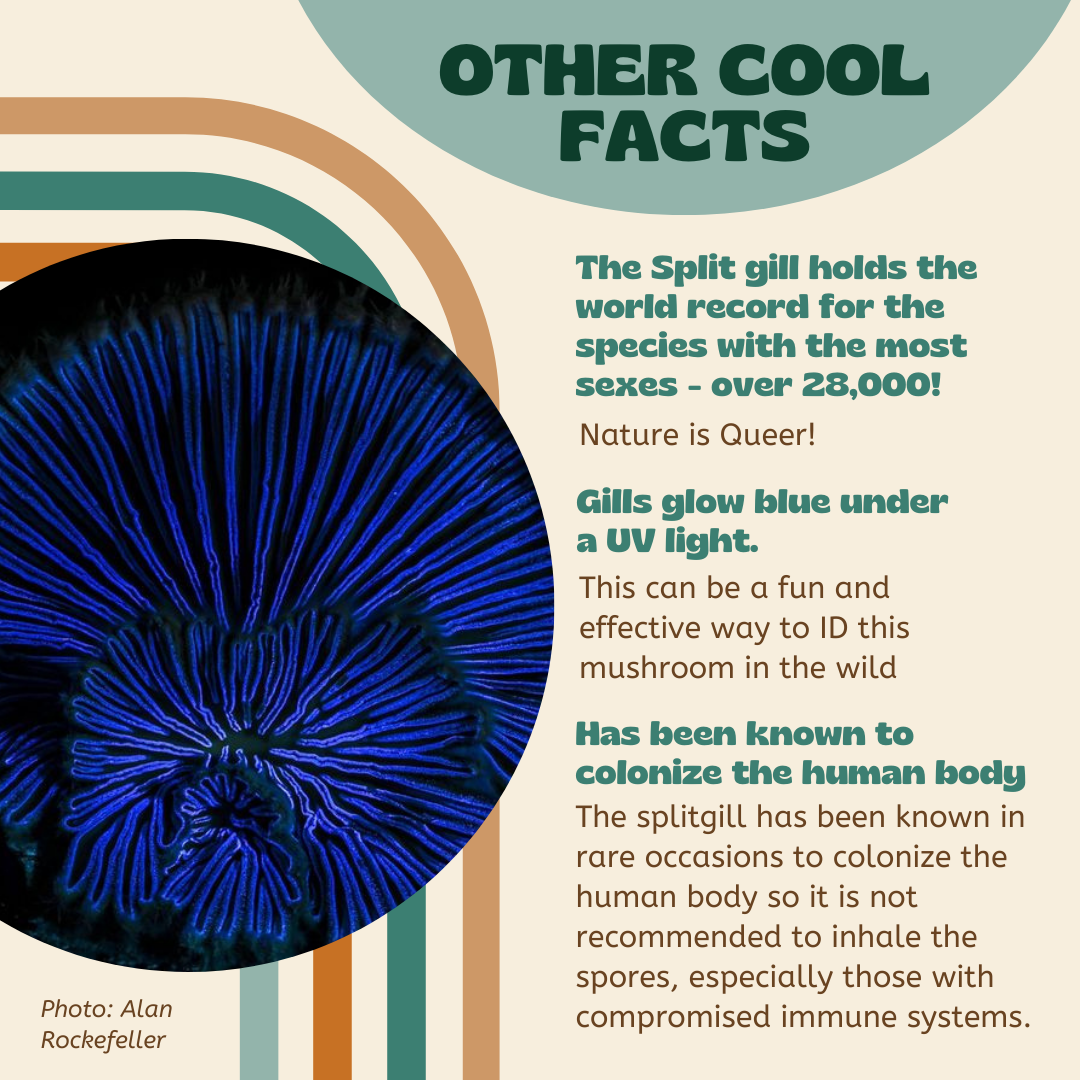

Other Cool FACTS

The Split gill holds the world record for the species with the most sexes - over 28,000! Nature is Queer!

Gills glow blue under a UV light. This can be a fun and effective way to ID this mushroom in the wild

Has been known to colonize the human body. The splitgill has been known in rare occasions to colonize the human body so it is not recommended to inhale the spores, especially those with compromised immune systems.

BECOME A SUPPORTING MEMBER & stay Dialed in with events & discover next month’s mystery mushroom

📸 Alan Rockefeller @forage.atx @inaturalistorg

February Foraging Forecast

Learn wild, edible mushrooms fruiting in Central Texas after rain.

Learn wild, edible mushrooms fruiting in Central Texas after rain.

WOOD BLEWIT Collybia species, formerly Lepista, Clitocybe

Distinct lilac to purple-pink color

Grows in and decomposes leaf duff

Light pink to white spores

Great in breakfast tacos

As the weather stays cool, look out for the edible Wood Blewit, Collybia nuda or tarda species (formerly Lepista and Clitocybe.) This distinct lavender-colored mushroom is found from fall through spring and fruiting in hardwood leaf duff which is decomposes. Fresh wood blewits are great with eggs in breakfast tacos. As they get older they become more tan and iridescent colored on the cap and taste bitter. I throw the older wood blewits my compost leaf pile because they are such great decomposers and will colonize and grow in hardwood leaf litter.

Look-alikes: Be warned because there are deadly, poisonous look-alikes in the Cortinarius or webcap family that grow in similar conditions. It's important to do a spore print AND also confirm the ID with an expert. The spores of the wood blewit are light pink to white and the spores of Cortinarius mushrooms are rust colored. See our blog post with lots of photos and details to help you identify this mushroom.

OYSTER Pleurotus ostreatus

Color can vary white, tan and gray

White to cream gills, run down stem

Cap fan shaped, 2"-8" across, white spores

Grows in clusters and decomposes hardwood

Delicious meat replacement in all types of cuisines

Look-alikes: Southern Jack-o-lantern, Omphalotus subilludens which is toxic and orange to brown in color.

WOOD EAR: Auricularia species

Grows in clusters on decaying hardwood after rain

Cap is wavy, ear-shaped to irregular, 1-4" and > 1/4" thick

Jelly texture and lacks gills or pores

Produces white spores

Absorbs flavors, great in soups, contains protein, iron, calcium and phosphorus

Edibility: Wood ear mushrooms are a popular ingredient in many Chinese dishes, such as hot and sour soup, and also used in Chinese medicine. It is also used in Ghana, as a blood tonic. Modern research into possible medical applications has variously concluded that wood ear has anti-tumor, hypoglycemic, anticoagulant and cholesterol-lowering properties.

Look-alikes: Amber Jelly, Exidia recisa which is also edible.

TURKEY TAIL Trametes versicolor

Variable coloration, distinct striping pattern

Grows in overlapping clusters on logs and stumps

No gills, pores are small and round, white to light brown

Tough, leathery flesh

Medicinal and can be brewed into a tea, broth, or extracted into a tincture.

Look-alikes: False turkey tail. or Stereum ostrea and is non-toxic. Mushroom Expert has a useful check list to determine if it is true medicinal turkey tail.

Become a member and learn more about wild mushroom foraging in Texas!

Membership benefits include early access and discounts to walks, workshops, and more. Your membership helps support the larger community! Tag us to get help with ID and add your observations to iNaturalist.org. If you are trying a new mushroom, confirm the ID with an expert, then try a small amount to make sure you don't have an allergic reaction. Texas Mushroom Identification Facebook group is great for quick responses and ID help. Also, don't forget to add your finds on the Mushrooms of Texas project on iNaturalist.